A Guide to Assignments for Library Research

Ways to think about assignments

Essential Questions

Avoiding plagiarism

Adapting to the Block Plan

Resources

Introduction: Ways of thinking about library research

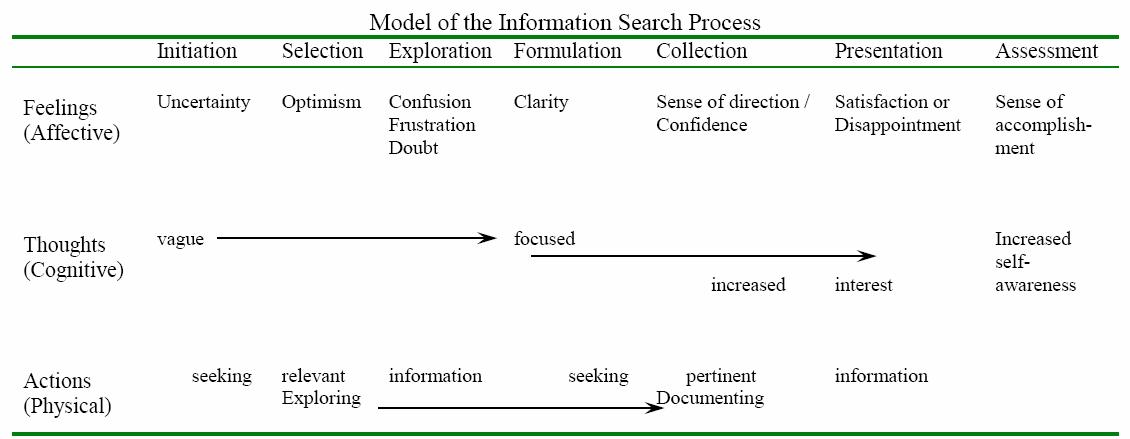

Research is an iterative process with several stages. Each stage is comprised of tasks to be accomplished. The researcher aims to move forward through these stages, but finds himself/herself stepping back to previous stages at times. As the student researcher engages in research tasks, certain feelings emerge. Often, students think that they are unique in how they feel about their research progress. It may be insightful for them to see that in fact they are typical. Carol Kuhlthau has studied student researchers of various ages and from that research she has developed a model that shows the tasks of the research process as well as the thoughts and feelings accompanying those tasks (Kuhlthau, 1993).

This model shows the range of feelings that the typical student researcher experiences. The points of anxiety, confusion, or frustration are times when intervention by an outsider can facilitate progress to the next stage of the process. The intervention might be by a peer, a professor, a librarian, a writing consultant, or a technology consultant. As library research assignments are created, instructors may want to plan to offer interventions at those critical points.

Students arriving at college bring notions about college library research as diverse as their overall high schools experiences. We do not always think about the messages we might send these student as we assign library research. Do we imply for them that the only thing that matters is the end product? Do we suggest to them that library research is about doing rather than about learning? Do we suggest that library research is something they do in isolation? What do they conclude from the way we construct and describe our expectations? As we think about our assignments these factors may be worthy of our consideration:

- What do we want them to learn about the research process?

- How can we develop in them skills and dispositions toward research that will transfer to future classes and experiences they will encounter?

- How can we help them see that research rarely occurs in isolation, but instead often involves consultations with experts-either in the discipline or in the process of research?

- How can we help them see the character of library research within a discipline as distinct from research in other disciplines?

- What alternatives might we consider for end-products resulting from student research?

In this guide, we attempt to raise our consciousness about the expectations we set in our library research assignments, the types of end products students might create, and the ways we might assess their work. We offer suggestions that may lead toward assignments that

- engage students at a variety of levels of complexity;

- encourage students to develop a sense of research as a process-not a finite task;

- engage students as active learners;

- explore the nature of library sources and research within a discipline;

- demonstrate how library research can benefit from collaboration and consultation;

- offer opportunities for both faculty and students to assess the assignment and the program;

- reduce the temptation for students to plagiarize; and

- take advantage of the potential of the block plan.

Librarians and writing consultants each have a unique vantage point in seeing assignments horizontally across disciplines and vertically within majors. However, it is faculty who design assignments and assess the end result of those assignments. This guide emphasizes and encourages collaborative work that includes faculty, librarians, writing consultants, and educational technologists to create assignments that challenge and engage students. We hope that this guide will be useful to all faculty and staff working to enrich the undergraduate experience.

Back to top

Section 1. Ways to think about assignments

Technology has both enhanced and challenged the design of library research assignments for college courses. On the one hand, technology facilitates access to an ever-expanding array of information that allows faculty to raise standards of excellence for library research. On the other hand, technology has created potential "shortcuts" to library research by offering papers online and an unjuried domain of easily-accessed information that behaves as something of a minefield for the naïve researcher where inaccurate or unauthoritative information is plentiful. In addition, the cut-and-paste capabilities of technology pose a constant temptation to the harried student to short-circuit the intellectual processing stage of research. As a result of this new information landscape, instructors are challenged to design assignments that engage students in library research in a meaningful and engaging way.

In thinking about assignments here, we will consider taxonomies of cognitive complexity, the concept of essential questions, strategies to avoid plagiarism, and qualities of good assignments for the block plan.

1. Taxonomies.

Taxonomies provide a way of classifying assignments. By considering classification, we can seek to provide students a range of assignments that engage them in different kinds of intellectual pursuits. Two classification schemes that might be useful here are Bloom's (1956) Taxonomy of Education Objectives and Wiggins and McTighe's (1998) Facets of Understanding.

Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives

- Knowledge: Remembering terminology or specific facts; dealing with specifics (conventions, trends and sequences, classifications and categories, criteria, methodology); learning abstractions in a field (principles and generalizations, theories and structures).

- Comprehension: Grasping the meaning of informational materials.

- Application: Using information in new and concrete situations to solve problems that have single or best answers.

- Analysis: Breaking down informational materials into their component parts; examining and trying to understand the organizational structure of information; identifying motives or causes; making inferences; and/or finding evidence to support generalizations.

- Synthesis: Creatively or divergently applying prior knowledge and skills to produce a new or original whole.

- Evaluation: Judging the value of material based on personal values/opinions, resulting in an end product, with a given purpose, without real right or wrong answers.

One way to think about Bloom's Taxonomy is to consider what the student will do to complete the assignment by examining the verbs we use in describing the expectation:

|

Knowledge

|

Comprehension

|

Application

|

Analysis

|

Synthesis

|

Evaluation

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Define

|

Classify

|

Apply

|

Analyze

|

Adapt

|

Appraise

|

|

Identify

|

Compare

|

Calculate

|

Compare

|

Categorize

|

Choose

|

|

List

|

Demonstrate

|

Chart

|

Contrast

|

Compile

|

Criticize

|

|

Name

|

Describe

|

Develop

|

Correlate

|

Compose

|

Defend

|

|

Recall

|

Differentiate

|

Illustrate

|

Deduce

|

Design

|

Estimate

|

|

Recognize

|

Explain

|

Interpret

|

Devise

|

Hypothesize

|

Evaluate

|

|

Show

|

Interpret

|

Manipulate

|

Diagram

|

Justify

|

Judge

|

|

State

|

Paraphrase

|

Modify

|

Distinguish

|

Report

|

Justify

|

|

Visualize

|

Summarize

|

Predict

|

Organize

|

Schematize

|

|

|

Trace

|

Relate

|

Outline

|

Support

|

||

|

Solve

|

Plan

|

Write

|

|||

|

Use

|

Prioritize

|

Wiggins and McTighe's Facets of Understanding

We give students assignments in hope that the experience will engage them and enhance their understanding of a discipline, concept, or issue. Mature understanding of a concept is described here as having six facets. In any given situation, understanding, according to these authors, is always a matter of degree. We can ask ourselves which of these facets of understanding are likely outcomes of our assignment:

- Explain: Does the assignment require the student to understand why and how?

- Interpret: Does the assignment require the student to show an event's significance, reveal an idea's importance, or provide an accurate interpretation?

- Apply: Does the assignment require the student to use the knowledge in a defined context?

- Have perspective: Does the assignment cause the student to see things from a dispassionate and disinterested perspective?

- Empathize to gain insight: Does the assignment cause the student to view a problem or situation from someone else's point of view?

- Have self-knowledge: Does the assignment require the student to self-consciously question himself/herself?

2. Essential Questions.

When we design assignments, we think about our intended purpose. One way of thinking about purpose is to ask ourselves, "What is the essential question we want students to consider as they engage in this assignment-the big idea?" These questions point to the core or essence of a discipline. Examples of essential questions are "Whose country is this, anyway?" or "Are mathematical ideas inventions or discoveries?" or "Does art reflect culture or shape it?" Essential questions are focused and complex. By considering the essential questions of our courses, we can then shape the central question that frames our assignments.

As we review the assignments for our courses, we might ask ourselves, whether we have designed an assignment that demands that students sustain a focus on a significant question. Two key words here are focus and significant. When students focus their library research, they have explored a topic generally and then have found an aspect or dimension that generates a research question-not just a topic. A significant question implies that the research question that underpins their library research is one that matters, that offers an answer to the question "So what?"

American Politics -- Calendar for Public Policy Paper Assignment

|

Block Calendar

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

WEEK #1

|

|||||

|

§§§

|

MONDAY

|

TUESDAY

|

WEDNESDAY

|

THURSDAY

|

FRIDAY

|

|

9:00 a.m.

|

|||||

|

1:00 p.m.

|

Research Methods:Finding Topics & Locating Sources* [Library Lab Session]

|

Policy Paper Topic and Working Bibliography Due by Noon Sunday**

|

|||

|

WEEK #2

|

|||||

|

§§§

|

MONDAY

|

TUESDAY

|

WEDNESDAY

|

THURSDAY

|

FRIDAY

|

|

9:00 a.m.

|

|||||

|

1:00 p.m.

|

Research Methods: Improving Your Sources*** [Library Lab Session]

|

Policy Recommendation & Outline of Contentions Due by Noon Sunday****

|

|||

|

WEEK #3

|

|||||

|

§§§

|

MONDAY

|

TUESDAY

|

WEDNESDAY

|

THURSDAY

|

FRIDAY

|

|

9:00 a.m.

|

Policy Paper Due @ Noon Today*****

|

||||

|

1:00 p.m.

|

|||||

|

WEEK #4

|

|||||

|

§§§

|

MONDAY

|

TUESDAY

|

WEDNESDAY

|

THURSDAY

|

FRIDAY

|

|

9:00 a.m.

|

|||||

|

1:00 p.m.

|

Policy Paper Rewrite Due @ 5 p.m.

|

||||

* Library instruction focused on exploring/narrowing a topic and locating and evaluating information sources.

** Both the professor and librarian reviewed the bibliographies, the professor giving feedback on sources/topic and the librarian structuring her subsequent instruction session to address specific problems/issues evidenced in the bibliographies.

*** Instruction focused on locating scholarly and primary sources as well as provided time for one-on-one research assistance.

**** Professor reviewed and gave feedback regarding whether the policy recommendation was sufficiently narrowed and contentions were clearly outlined with supporting evidence, suggesting further research and individual consultations with the librarian and writing consultants if deemed necessary.

***** Professor gave considerable feedback regarding revisions and sometimes suggested further research, again referring students to the librarian and writing consultant for assistance.

3. Avoiding plagiarism.

Assignments can invite plagiarism if they do not engage students in inquiry that calls for more than reporting factual information that is readily available elsewhere. As we review our assignments we can ask ourselves whether the end product could be available in a reference book or a website or other publication. If it can, then chances are we have not developed an assignment that will engage our students adequately and we have therefore increased the potential for plagiarism to occur. Some strategies for avoiding plagiarism as we design assignments include:

- Require students to narrow their topics. Papers available for downloading or purchase are usually very general in scope.

- Require specific components. Requiring a specific slate of sources ("…two scholarly journals, two books, and a source from the Internet…") reduces the possibility a student can purchase a paper that meets those requirements.

- Require photocopies or printouts of sources cited. Even if a student has purchased a paper that meets your requirements, s/he will learn quite a bit about the research process by tracking down each source cited in the paper!

- Require discussion or presentation of the paper. Asking students to informally discuss their papers with their peers lets them know they must have first-hand knowledge of their topic.

- Personalize or localize the assignment. Asking students to relate their research findings to a personal observation or experience inherently requires original work.

- Require an in-class meta-learning essay. When the paper is handed in, ask students to write an in-class essay discussing and evaluating what they learned from the research and writing processes.

- Require a consultation with a librarian. By scheduling each student to meet with a librarian at a given stage of the research project they are more likely to develop the focus of the project or to review sources of information.

- Encourage the use of RefWorks for managing sources. Use of a bibliographic manager may encourage students to cite more accurately and appropriately when the mechanics of the process are automated.

- Stage the assignment. Requiring students to meet short-term deadlines for a major research project helps the instructor observe the student's stages of work; setting intermediate dates for submitting elements such as the research question, the preliminary source list, or a draft of the paper highlights the process of research and not just the final product.

- Review specific citation requirements for your discipline. Although students may be aware of different citation styles such as the APA, MLA and Chicago, few know that when and how sources are cited vary from one discipline to another.

- Include explicit statements about plagiarism in your syllabus. For example:

-

WHY CITE SOURCES? By citing the source(s) of information you are using in a paper, you are (1) acknowledging from where/whom the information came, and (2) providing the necessary information to the reader for finding the original source(s) if s/he wishes to do so. Whether or not you directly quote from a source or paraphrase in your own words the author's ideas, you must acknowledge from where/whom that information came by providing an in-text citation to the source as well as a citation in your bibliography at the paper's end. Failure to cite your sources constitutes plagiarism, as without citations you are falsely representing the idea as your own.

While these strategies may help avoid plagiarism, they may also serve additional purposes in helping students learn more from their research experience and use their time and resources wisely.

Back to top

4. Adapting to the Block Plan.

While design of assignments is an important aspect of pedagogy in all institutions, a short and intensive term is a special factor for consideration. These strategies help create assignments that may be more effective in such abbreviated course calendars:

- Stage the assignment. To help students use their time wisely, set deadlines throughout the term for the stages of the research process to protect students against procrastination and also to allow several timely points of intervention to address problems/issues.

- Focus/depth. Maximize the potential for depth of investigation (in contrast to breadth). Engage a librarian to work with students on strategies for narrowing a topic. Using the thesaurus of a specialized database, browsing articles and examining subject headings, focusing on a narrower time span, a smaller place, a specific group of people, a specific event, or specific individual are all strategies for controlling a research topic.

- Flexible time. Use the flexibility inherent in students taking one course only to schedule work sessions facilitated by faculty, Writing Center staff, or librarians at various stages of the assignment.

- Localize the experience. Take students to off-campus resources to collect data or to explore primary (e.g., local interviews, observations) or secondary sources (e.g., museums, special libraries, or archives).

Bloom, B.S. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals,

by a Committee of College and University Examiners. New York: Longmans, Green.

Kuhlthau, C. C. (1993). Seeking Meaning. Ablex.

McCabe, D. and Pavela, G. (May/June 2004). "Ten (Updated) Principles of Academic Integrity; How

Faculty Can Foster Student Honesty," Change 36/3: 10-15.

Parker-Gibson, N. (Spring 2001). "Library Assignments," College Teaching 49/2: 65-70.

Sterngold, A. (May/June 2004). "Confronting Plagiarism; How Conventional Teaching Invites Cyber-

cheating," Change 36/3: 10-15.

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding by Design. Alexandria, VA: Association for

Supervision and Curriculum Development.