|

|

|---|---|

|

Dyskolos and It Happened One Night Structure |

Here is an itemized list containing all of the different parts of the Greek comedy Birds. The parts of the structure are in bold , followed by some information about how the plot line and structure of Aristophanes’ Birds fits into the framework.

Prologue(lines 1-295)

As the play starts we see two old men walking around, through their speech the audience comes to learn that they have been walking for several days. It also becomes apparent that they are seeking somewhere that will be better than Athens, where they have all sorts of restrictions, laws and taxes. The audience is told that the men intend to consult Tereus, a man turned bird, as to where a good place to live might be. All of this dialogue between Makemedo and Goodhope serves an expository function, in the sense that it is telling the audience the raw information that they need to know in order to understand the characters’ intentions. In addition to setting up the basic plot elements, Aristophanes also warms the audience up to the ornithological theme of the play. Several of the lines between the two contain bird references and imagery. Goodhope asks Makemedo what the point of the “wild-goose chase” that they are involved in is. Goodhope says that he is “sick as a parrot” of living in Athens and that is why he and his friend have “flown [their] country’s coop.” In the very first interaction between the main comic subjects and another speaking role comes when the men are surprised the servant of the Hoopoe. Upon being confronted by the servant, the two old men involuntarily urinate and defecate. This hilarious part lets the audience have a good laugh and settle into the comedic nature of the play. Also in this initial interaction Makemedo is incredibly rude and insulting to the servant, he makes a joke about how he gives the Hoopoe sexual favors. This exchange shows the audience Makemedo’s generally curt and demeaning attitude when talking to others. While talking to the Hoopoe, the two men are not satisfied with the alternatives to Athens that he suggests, and all of a sudden Makemedo suddenly has the idea of trying to convince the Hoopoe to start a city of birds, where the two geriatrics could live disguised as birds. This off the cuff decision sets the first major goal of the play into motion. One could contend that this abrupt plot twist is the first instance of how elastic and spontaneous the Birds story line is. The play then transitions from prologue to parados in the Hoopoe’s speech (lines 227-262) when he beckons all of his fellow birds to come out.

Parados(lines 296-461)

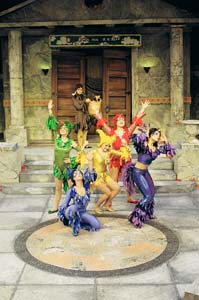

Bernhard Zimmermann suggests that Aristophanes’ parodoi fall into three distinct categories. The parados of Birds fits nicely into the second type, according to Zimmermann, sharing characteristics with the works Knights, Peace and Plutus. The birds appear, a marvelous display of costumes for sure, without knowing why they are summoned. They are hostile at first after hearing what Makemedo wants of them, since birds are natural enemies of humans, which results in the battle scene. But eventually, after the Hoopoe’s intervention, the birds agree help Makemedo. In this way, the chorus in the Birds parados displays the characteristic of providing aid to the comic subject, a characteristic that is seen in other Aristophanic comedies.

Agon(lines 462-635)

K.J. Dover’s ingredients of an agon will be useful in understanding the below information.

The agon in Birds is unique in that Makemedo is the only contestant. The birds usher in this little contest of mental might in with the two lines “Now speak human. Let us consider what you are proposing/ Don’t worry, we will not be the first ones to breach the treaty.” One could think of Makemedo as competing with himself, trying to persuade all of the birds with no previous preparation that they are the true rulers of the earth and are the rightful bearers of Zeus’ scepter. Goodhope occasionally interjects with his two cents. It is quite possible that given the birds’ previous hatred towards the humans that the feathered ones will peck Makemedo to death if his reasoning isn’t solid enough. Because of this danger, Birds unique one-contestant agon holds the same immediacy and heightened state as the typical debate agon. This agon isn’t epirrhematic, meaning it doesn’t revolve around matters of public concern, as is the agon is Lysistrata. Regardless, Makemedo still produces a multitude of excellent, extremely clever and delightful pieces of evidence for why birds should be better than even the gods. The number of ridiculous reasons for total bird domination that Makemedo applies a fantastical logic to is quite incredible. How did Aristophanes think of all these? The birds lyric stanza (lines 629-635) corresponds to Dover’s sixth ingredient, it is a response and comment on the performance of the contestant.

Parabasis(1 st: lines 675-801, 2 nd: lines 1058-1118)

Birds has an additional parabasis a little bit after the first one. Both of the chorus only sections are speech in a highly dramatic style about the superiority of birds to humans. The level the language and content the chorus stay at during this section is highly abnormal. Usually the playwright includes a jocular section early in the parabasis that is an advertisement for himself and a put-down towards his rivals in an effort to gain first prize in the City Dionysia. Here this self-promotion doesn’t come until the very end of the second parabasis. Perhaps the reason Aristophanes kept the parabasis so highly dramatic until the very end was to give great power to the message that is behind the speech. This is not to say that Aristophanes actually thought that birds should hold dominion over humans, but perhaps he wanted to guide the audience through a little exercise that would grade away any excessive pride that they might have. Many tragedies certainly make warnings against the dangers of hubris, it seems this highly formal section of the comedy may be doing the same.

Episodes

In the remainder of the play, the action follows a steady course of overcoming obstacles in order to achieve the goal of establishing Cloudcuckooland. After the parabasises around seventeen new characters are introduced, most of who are getting in the way of the creation of Makemedo’s bird utopia. Once the news of the successful creation of Cloudcuckooland, the excitement that is left centers around how the gods will react to this city and to what extent the birds will triumph over them. Many elements of Athenian life that are generally held in a respectable light are demeaned in the episodes following the parabasis. Individuals who hold esteemed positions are lampooned: the lawyer, the mathematician, the inspector, the preist, etc.. Also, the sacred is made to look silly and rather powerless. Iris visits to threaten destruction only to be insulted by Makemedo and angrily run off stage.

Exodus

By the end of the play we see how the idea of having a utopia has failed. Cloudcuckooland has become just another Athens, still bound by restrictions, laws and taxes. The comic subject however has gained ultimate power. The representation incarnate of this power is the goddess Basileia, whom Makemedo weds. The marriage ceremony is the exodus of Birds. Sources: Dover, K.J.. Aristophanic Comedy. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1972. Zimmermann, Bernhard. "The Parodoi of the Aristophanic Comedies". Oxford Readings in Aristophanes. Ed. Erich Segal. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. 182-193.

|

For questions or comments, please contact John Gruber-Miller |

|